Indigenous Ecotourism and Sustainable Development:

The Case of Río Blanco, Ecuador

David T. Schaller

Department of Geography

University of Minnesota

|

Note: This paper is based on research I conducted in 1995. I have not worked

in ecotourism research since then, so please don't ask me about current trends

in the field!

Versión Español

- Physical and Human Geography of Napo Province

- The Association of Río Blanco

- Case Study Methods: Quichua Interviews

- The Struggle for Land Tenure

- A Growing Community

- The Expansion of Agriculture

- The Reserves

Summary:

The indigenous Quichua community of Río Blanco, in the Ecuadorian

Amazon (Napo Province), was founded in 1971 by Quichua migrants from the Andean

foothills, where, as a result of population growth and inmigration of mestizo

agricultural colonists, the supply of land was becoming short. Since 1971, the

economy of Río Blanco has shifted from one based almost entirely on subsistence

agriculture and hunting to one reliant on cash crops such as coffee, cacao,

rice and maize. Río Blanco has experienced high population growth in

the past twenty years which, along with a rising cost of living, has driven

the people of the community to expand greatly the amount of land under cultivation.

As a result, the amount of primary tropical forest has decreased until, in 1995,

it accounted for less than half of the community's main block of land. Facing

continued population growth, the community has developed an ecotourism project

as an alternative economic activity which may protect the forest rather than

clear it.

Summary:

The indigenous Quichua community of Río Blanco, in the Ecuadorian

Amazon (Napo Province), was founded in 1971 by Quichua migrants from the Andean

foothills, where, as a result of population growth and inmigration of mestizo

agricultural colonists, the supply of land was becoming short. Since 1971, the

economy of Río Blanco has shifted from one based almost entirely on subsistence

agriculture and hunting to one reliant on cash crops such as coffee, cacao,

rice and maize. Río Blanco has experienced high population growth in

the past twenty years which, along with a rising cost of living, has driven

the people of the community to expand greatly the amount of land under cultivation.

As a result, the amount of primary tropical forest has decreased until, in 1995,

it accounted for less than half of the community's main block of land. Facing

continued population growth, the community has developed an ecotourism project

as an alternative economic activity which may protect the forest rather than

clear it.

- What is Ecotourism?

- Tourism in Napo Province

- A Model for Indigenous Ecotourism Development

Summary: Ecotourism has attracted increasing attention in recent

years, not only as an alternative to mass tourism, but as a means of economic

development and environmental conservation. Proponents and some scholars

believe that it can potentially focus the benefits of tourism on the local

population and environment while minimizing negative impacts. Other observers

remain skeptical, warning that ecotourism has not yet been proven to be either

beneficial or sustainable. A growing number of researchers agree that local

control is key to avoiding many problems resulting from ecotourism development.

By scaling down production processes and returning power to local units of

governance, ecotourism may reduce economic leakages, minimize negative impacts

and concentrate the benefits locally. However, the international nature of

tourism creates many obstacles for localities wishing to maintain control of

their tourism industry. Too often, local people have neither the political

power nor the business connections to compete at an international level with

metropolitan tour agencies. Nevertheless, ecotourism's rapid growth has

attracted the attention of many people and communities in low-income countries.

In the Ecuadorian Amazon, a growing number of indigenous Quichua communities are

turning to ecotourism as an alternative to expanded commercial agriculture. Río

Blanco has joined a network of Quichua communities which are developing their

own ecotourism projects.

- Communal by Design

- Case Study Methods: Tourist Interviews

- Perceptions of the Tropical Forest

- Accuracy of the Ecotourism Experience

- Authenticity of the Ecotourism Experience

Summary:

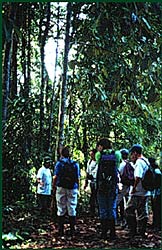

Two main tenets of Río Blanco's project are communal control

and small scale. Work is assigned equitably so all member-families of Río

Blanco contribute to and benefit from ecotourism. In the project's first year,

150 tourists visited. Each family earned about $100 in the first year, or about

one-fifth of their income for the year. Most members would like to receive about

300 tourists in 1996, thus maintaining the project's small scale. Tourists visiting

Río Blanco range from small groups of independent tourists to students

and teachers in groups of ten or twenty who are part of a tour run by a nearby

biological field station. A group of fifteen students interviewed after their

visit expressed satisfaction with their experience in Río Blanco, though

evidence suggests that their visit did not give them an accurate portrayal of

contemporary Quichua life. Whereas the people of Río Blanco rarely spend

time in primary forest, owing to their agricultural obligations, tourists spend

virtually all their time in primary forest. Few tourists interviewed believed

that commercial agriculture was a significant part of the community's economy,

indicating that they had learned little about a central aspect of community

life.

Summary:

Two main tenets of Río Blanco's project are communal control

and small scale. Work is assigned equitably so all member-families of Río

Blanco contribute to and benefit from ecotourism. In the project's first year,

150 tourists visited. Each family earned about $100 in the first year, or about

one-fifth of their income for the year. Most members would like to receive about

300 tourists in 1996, thus maintaining the project's small scale. Tourists visiting

Río Blanco range from small groups of independent tourists to students

and teachers in groups of ten or twenty who are part of a tour run by a nearby

biological field station. A group of fifteen students interviewed after their

visit expressed satisfaction with their experience in Río Blanco, though

evidence suggests that their visit did not give them an accurate portrayal of

contemporary Quichua life. Whereas the people of Río Blanco rarely spend

time in primary forest, owing to their agricultural obligations, tourists spend

virtually all their time in primary forest. Few tourists interviewed believed

that commercial agriculture was a significant part of the community's economy,

indicating that they had learned little about a central aspect of community

life.

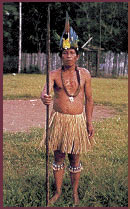

However, many tourist-respondents were confused and even

upset by the cultural program, in which the people of the community wore the

traditional grass skirts and red body paint of their ancestors and performed

traditional Quichua music and dances. Many tourist-respondents questioned the

authenticity of these performances, since they appeared incongruent with

contemporary Quichua life. These concerns echoed scholarly research into

tourism and authenticity, which postulate both a touristic need for authenticity

and the ubiquity of "staged authenticity," which may only frustrate

the earnest seeker of true authenticity. Ironically, in Río Blanco the

rediscovery of traditional music and dance for tourism purposes may well lead to

its reincorporation into community festivals, increasing its authenticity in the

tourism program.

- Ecotourism as Development, Part One

- The Benefits and Costs of Ecotourism Development

- Ecotourism as Development, Part Two

- Threats to Ecotourism's Sustainability

- The Means and the Ends

Summary: The potential of Río Blanco's ecotourism project as

sustainable, appropriate development currently appears strong. While not all

Quichua respondents indicated that they saw the connection between tourism

development and forest preservation, a growing conservationist ethic among

members suggests that such a linkage may be evolving. It remains unclear,

however, how this ethic will affect agricultural activity. Most respondents

reported that they would rather increase tourism than agricultural production,

but nearly half also said they intended to clear more forest for cultivation.

Many members may have difficulty accepting the opportunity costs of further

ecotourism development. Until the community decides how much trust it can place

in ecotourism as a reliable and sustainable economic activity, agriculture will

probably continue to expand.

In

the evaluation of development schemes, what is of prime importance for both

community members and the coordinators of Quichua ecotourism projects is the

survival of Quichua culture. If Río Blanco's ecotourism project does

not disrupt established social and political structures of the community, it

may qualify as appropriate development even though it is not a traditional form

of development. Furthermore, it may serve as a tool to help rural Quichua learn

business skills which are crucial if they are to succeed in dealings with mestizo

residents of the area as well as with other Ecuadorian and foreign parties.

In this way, ecotourism may not be an end in itself but merely a bridge to the

future. The sustainability of a particular ecotourism project may be irrelevant

in the long run. What matters is its impact on the local people and environment,

and how well it serves them against the challenges ahead.

In

the evaluation of development schemes, what is of prime importance for both

community members and the coordinators of Quichua ecotourism projects is the

survival of Quichua culture. If Río Blanco's ecotourism project does

not disrupt established social and political structures of the community, it

may qualify as appropriate development even though it is not a traditional form

of development. Furthermore, it may serve as a tool to help rural Quichua learn

business skills which are crucial if they are to succeed in dealings with mestizo

residents of the area as well as with other Ecuadorian and foreign parties.

In this way, ecotourism may not be an end in itself but merely a bridge to the

future. The sustainability of a particular ecotourism project may be irrelevant

in the long run. What matters is its impact on the local people and environment,

and how well it serves them against the challenges ahead.

Interested in visiting Río Blanco?

This research was supported by a fellowship from the Department of Geography, University of Minnesota.

Contact: David@Schaller.com

to

Ecotourism Research Home Page

to

Ecotourism Research Home Page

Summary:

The indigenous Quichua community of Río Blanco, in the Ecuadorian

Amazon (Napo Province), was founded in 1971 by Quichua migrants from the Andean

foothills, where, as a result of population growth and inmigration of mestizo

agricultural colonists, the supply of land was becoming short. Since 1971, the

economy of Río Blanco has shifted from one based almost entirely on subsistence

agriculture and hunting to one reliant on cash crops such as coffee, cacao,

rice and maize. Río Blanco has experienced high population growth in

the past twenty years which, along with a rising cost of living, has driven

the people of the community to expand greatly the amount of land under cultivation.

As a result, the amount of primary tropical forest has decreased until, in 1995,

it accounted for less than half of the community's main block of land. Facing

continued population growth, the community has developed an ecotourism project

as an alternative economic activity which may protect the forest rather than

clear it.

Summary:

The indigenous Quichua community of Río Blanco, in the Ecuadorian

Amazon (Napo Province), was founded in 1971 by Quichua migrants from the Andean

foothills, where, as a result of population growth and inmigration of mestizo

agricultural colonists, the supply of land was becoming short. Since 1971, the

economy of Río Blanco has shifted from one based almost entirely on subsistence

agriculture and hunting to one reliant on cash crops such as coffee, cacao,

rice and maize. Río Blanco has experienced high population growth in

the past twenty years which, along with a rising cost of living, has driven

the people of the community to expand greatly the amount of land under cultivation.

As a result, the amount of primary tropical forest has decreased until, in 1995,

it accounted for less than half of the community's main block of land. Facing

continued population growth, the community has developed an ecotourism project

as an alternative economic activity which may protect the forest rather than

clear it. Section

2: Ecotourism in theory and practice

Section

2: Ecotourism in theory and practice Summary:

Two main tenets of Río Blanco's project are communal control

and small scale. Work is assigned equitably so all member-families of Río

Blanco contribute to and benefit from ecotourism. In the project's first year,

150 tourists visited. Each family earned about $100 in the first year, or about

one-fifth of their income for the year. Most members would like to receive about

300 tourists in 1996, thus maintaining the project's small scale. Tourists visiting

Río Blanco range from small groups of independent tourists to students

and teachers in groups of ten or twenty who are part of a tour run by a nearby

biological field station. A group of fifteen students interviewed after their

visit expressed satisfaction with their experience in Río Blanco, though

evidence suggests that their visit did not give them an accurate portrayal of

contemporary Quichua life. Whereas the people of Río Blanco rarely spend

time in primary forest, owing to their agricultural obligations, tourists spend

virtually all their time in primary forest. Few tourists interviewed believed

that commercial agriculture was a significant part of the community's economy,

indicating that they had learned little about a central aspect of community

life.

Summary:

Two main tenets of Río Blanco's project are communal control

and small scale. Work is assigned equitably so all member-families of Río

Blanco contribute to and benefit from ecotourism. In the project's first year,

150 tourists visited. Each family earned about $100 in the first year, or about

one-fifth of their income for the year. Most members would like to receive about

300 tourists in 1996, thus maintaining the project's small scale. Tourists visiting

Río Blanco range from small groups of independent tourists to students

and teachers in groups of ten or twenty who are part of a tour run by a nearby

biological field station. A group of fifteen students interviewed after their

visit expressed satisfaction with their experience in Río Blanco, though

evidence suggests that their visit did not give them an accurate portrayal of

contemporary Quichua life. Whereas the people of Río Blanco rarely spend

time in primary forest, owing to their agricultural obligations, tourists spend

virtually all their time in primary forest. Few tourists interviewed believed

that commercial agriculture was a significant part of the community's economy,

indicating that they had learned little about a central aspect of community

life. In

the evaluation of development schemes, what is of prime importance for both

community members and the coordinators of Quichua ecotourism projects is the

survival of Quichua culture. If Río Blanco's ecotourism project does

not disrupt established social and political structures of the community, it

may qualify as appropriate development even though it is not a traditional form

of development. Furthermore, it may serve as a tool to help rural Quichua learn

business skills which are crucial if they are to succeed in dealings with mestizo

residents of the area as well as with other Ecuadorian and foreign parties.

In this way, ecotourism may not be an end in itself but merely a bridge to the

future. The sustainability of a particular ecotourism project may be irrelevant

in the long run. What matters is its impact on the local people and environment,

and how well it serves them against the challenges ahead.

In

the evaluation of development schemes, what is of prime importance for both

community members and the coordinators of Quichua ecotourism projects is the

survival of Quichua culture. If Río Blanco's ecotourism project does

not disrupt established social and political structures of the community, it

may qualify as appropriate development even though it is not a traditional form

of development. Furthermore, it may serve as a tool to help rural Quichua learn

business skills which are crucial if they are to succeed in dealings with mestizo

residents of the area as well as with other Ecuadorian and foreign parties.

In this way, ecotourism may not be an end in itself but merely a bridge to the

future. The sustainability of a particular ecotourism project may be irrelevant

in the long run. What matters is its impact on the local people and environment,

and how well it serves them against the challenges ahead. to

Ecotourism Research Home Page

to

Ecotourism Research Home Page