|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

One Size Does Not Fit All:

|

| Activity Type | Learning Style |

|---|---|

| Role-Play Allows users to adopt a persona and interact with other characters. |

Social Might prefer this since information is gathered from other characters in the activity. |

| Simulation Employs a model of the real world that users can manipulate to develop an understanding of a complex system. |

Intellectual Might find an abstract representation of the world more readily appealing. |

| Puzzle-Mystery Involves analysis and deductive reasoning to reach a logical conclusion. The user relies on evidence from people, nature, or reference material. |

Practical Might be attracted to problem-solving in the real world. |

| Design Emphasizes open-ended inquiry and experimentation, with a personal creation as the product of the experience. |

Creative Might be more engaged by the opportunity to create something unique. |

| Interactive Reference Provides multimedia content in a topical or thematic structure, for self-directed browsing. |

Intellectual Might appeal to those with self-motivated research goals. |

| Discussion Forum Facilitates interpersonal communication among users and subject experts. |

Social Might be preferred as an opportunity to interact with other people. |

We also hypothesized that if an activity type aligned well with a user's learning style, the user would perceive that activity to be more like play than work, whereas activities that did not easily align with learning style would be perceived to be more like work.

Our research focused on children age 10-13 (hereafter referred to as "children"), but we gathered data from all ages, allowing us to test our hypotheses with both children and adults.

Methods

Kolb's 12-question Learning Style Inventory (LSI) has been validated

for high school-age youth (ages 14-18) and adults (Kolb et al., 2000). Our

first step was to modify the LSI for use by our target audience of children

age 10-13. We changed eight words to simpler terms. We then deployed an on-line

survey consisting of the modified LSI plus age and gender questions. Figure

2 shows a sample question from the Flash-based survey, which was designed

to be more fun and interactive than Kolb's paper-based LSI in order to appeal

to our younger audience. We used the results of this survey to create a normalized

distribution of learning styles for children, such that each learning style

was represented by 25% of the sample.

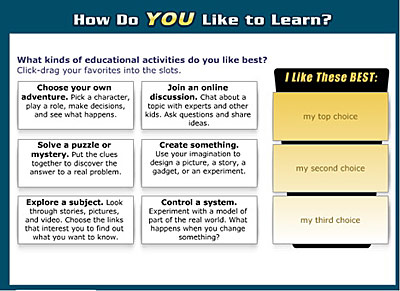

We also piloted a two-sentence description of each activity type, refining each for maximal understanding by middle school students. We then ran a preliminary on-line survey that asked respondents to rank order their three preferred activity types based on our written descriptions of the activities and to take the LSI. Figure 3 shows how respondents were asked to rank order their top three activity types.

This survey was placed on several eduweb sites and linked from 11 additional museum sites. The survey ran from June to October 2005 and collected a sample of 3013 respondents: 1226 middle-school-aged, 545 high school, and 1242 adults. Applying the normalized distribution to these data, we found significant correlations between learning style and activity preference. Individuals whose scores fell on an axis between style quadrants were eliminated.

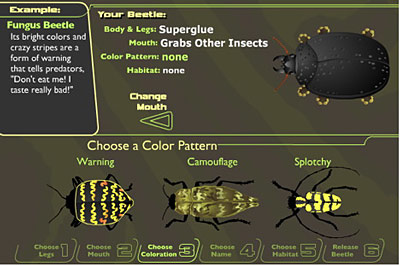

In the next phase of research, five of eduweb's existing educational activities, all dealing with the topic of animal ecology, were selected, abridged, and modified to provide brief (3-4 minute) experiences that exemplified five of the six activity types: Design, Role-Play, Puzzle-Mystery, Simulation, and Interactive Reference. The sixth type, Discussion, was omitted since it did not lend itself to one-way interaction and proved least popular in the preliminary survey. Figure 4 shows a sample screen of the Design activity.

A laboratory-style face-to-face study of 154 children (age 10-13) was conducted with groups visiting The Franklin Institute Science Museum and at a nearby school (Friends Select School). The study consisted of the activity type rank ordering and the LSI (as in the on-line survey), followed by the sample activities (presented in randomized sequence) and a Likert scale rating for each one. Interviewers asked all the children to discuss their ratings and to explain what they liked and did not like. In addition, children placed each activity on a 5-point bipolar scale (semantic differential) from play to work. Results of the laboratory study gave us insight into the aspects of the activities that appealed to individuals with each of the learning styles. The laboratory study also gave us interesting illustrative quotes from children.

A second on-line survey, also linked from multiple eduweb and museum sites around the country, was conducted from May to November 2006 and produced a sample consisting of 1161 middle-school aged children, 376 high school aged children, and 1056 adults. This survey was similar to the lab study, but since subjects did not necessarily complete all five of the sample activities, they were not asked to rank order the activities, and were scored only for the activities they did complete. T-tests and X2 tests determined that there were no significant differences in the populations by number of activities completed. The raw sample (with the exception of subjects who scored 0 on either axis) was used to calculate frequencies of learning styles in the population. All other tests for correlation used the normalized distribution. Results of this on-line survey are reported below.

Results

Distribution of Learning Styles

There is a marked variation in the distribution of learning styles among

children aged 10-13, in comparison to adults. Over two-thirds of all children

are Active learners with a Practical or Social learning style. In comparison,

the majority of adults are Abstract learners exhibiting Intellectual or Practical

learning styles. Kolb's research on teens and adults shows a similar shift

towards abstraction as people get older (Kolb 2005). It is interesting that

the Practical learning style, at the intersection of Active and Abstract,

is the most common style for both children and adults.

Comparing age groups, children are more likely to have a Social learning style, while adults are more likely to have an Intellectual style (Figure 5). This pattern reflects the shift toward Abstract and Reflective modes as people mature.

With respect to gender and learning style, we found no difference between boys and girls. Among adults, on the other hand, more adult females had a Social learning style in comparison to adult males.

Age, Gender, and Activity Preference

Based on responses to our brief written descriptions (not the sample activities

themselves), there is significant variation in activity preference by age

group (Figure 6). Children prefer Role-Play (30%) and Design (29%) activities

over the other activities. Adults prefer Interactive Reference (33%) and

Puzzle-Mystery (24%).

Gender also plays a role. Among children aged 10-13, boys prefer Role-Play significantly more than girls do, while girls prefer Design more than boys do. These differences affect the average ranking of the two activities: Role-Play and Design were ranked first and second by boys, and vice versa by girls. However, these gender differences are secondary to the influence of age. When considering children and adults together, gender no longer predicts activity preference. Girls are more like boys of their age, in that both prefer Design and Role-Play, than they are like adult women, who, like adult men, prefer Interactive Reference and Puzzle-Mystery. Therefore age remains the dominant factor in determining activity preference.

Note that these relationships are statistically significant in that they differ from what would be expected in the sample using X2, but the relationships are relative to other groups and should not be equated with popularity. For example, girls preferred Discussion more than did boys, but Discussion is the least popular of the six activity types. Only 6% of children and 3% of adults chose Discussion as their favorite activity. Each activity has a degree of appeal for a given audience. Chi squares compare various categories of user (e.g. child/adult, male/female, and the four learning styles), whereas Figure 6 shows frequencies of preferences within the population.

Learning Style and Activity Preference

There are significant relationships between learning style and preferences

for on-line educational activities.

Children

Figure 7 shows the following relationships between learning style and activity

preference among children:

These two associations support our research hypotheses. However, there were no significant associations for Creative or Practical learners within our target age group (10-13).

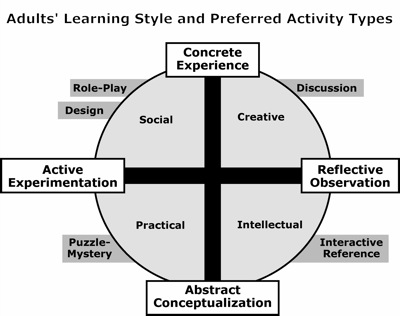

Adults

The relationship between learning style and activity preference is stronger

in the adult age group. Among adults, all four learning styles are associated

with activity preferences. Figure 8 shows the following relationships between

learning style and activity type preference among adults:

These results generally support our hypotheses. Three of our predictions are borne out:

Two additional associations are close to our predictions:

Both Social and Creative are on the Concrete side of the Concrete-Abstract axis, but differ on the Active-Reflective axis. Both Design and Discussion involve active participation as well as reflective contemplation. Respondents appear to have reacted to different aspects of these two activity types than we predicted.

Sample Activity Rating and Play/Work Score

When testing the sample activities, children nearly always liked those

activities that they scored as high in play value. That is, children gave

high activity ratings to the same activities that they thought were more

like play than work. Play value seems to be more influential than learning

style in predicting children's responses to a given activity.

Adults, however, do differentiate between the two ratings. On average, adults gave each activity a play/work score that was similar to that given by children. But their activity ratings did not follow suit. For example, adults scored Role-Play as second in play value, but last in activity rating – behind Simulation and Interactive Reference, which had lower play scores. Play, it seems, is a secondary consideration for adults, with Simulation and Interactive Reference offering something valuable to adults that overrides the appeal of play.

In modifying activities for use in this research, we sought to emphasize the core attributes of each activity type, rather than to strengthen its play value. It would certainly be possible to design a simulation with high play value if that was a goal. A commercial game like The Sims is a good example of just such a thing.

Conclusions

While museums and informal learning institutions have embraced the Web

as a medium for public outreach and education, we still are grappling to

understand our on-line audiences in their rich diversity and individual uniqueness.

This research identifies several important factors that developers should

consider when creating computer-based learning materials. Our central hypothesis,

that activity preference and learning style are related, has been confirmed

for adults. This relationship is weaker for middle school-age children, presumably

because their learning styles are not yet as fully solidified as adult's

learning styles. We have also found that activity preferences differ significantly

between groups of children and adults. Finally, gender differences in activity

preferences are weaker than learning style or age.

Learning Style

Learning style is indeed a major determinant of adult activity preference.

The adult preference for Interactive Reference supports our previous findings

that many adults have instrumental information-seeking goals for their on-line

activities (Schaller et al. 2004). Adults' preference for Puzzle-Mystery

accords with the widespread popularity of puzzle-type

"casual games" such as Bejeweled and Solitaire among adults on- and off-line.

It remains an interesting challenge for informal education developers to

create Puzzle-Mystery content for adults that contains both casual game puzzle-solving

elements and real-world educational content.

Children, on the other hand, do not have as strongly-differentiated learning styles, and the relationship between learning style and activity preference for children appears to be correspondingly less strong.

Age Group

While the data and statistical analysis employed for this paper do not

allow us to tie activity preference or learning style to a particular age,

it is clear that the relationship between learning style and activity preference

is different in children and adults. Other factors besides learning style

shape people’s activity preferences. Children scored our sample Design and

Role-Play activities as being most like play on the play/work continuum;

they also gave these two activity types the highest overall ratings. Play

value seems to be more important than learning style for children.

Gender

With regard to gender differences, there has been considerable discussion

about designing girl-friendly video games and other electronic media (Chu

et al. 2004). We found some influence of gender on children's activity preferences,

with boys preferring Role-Play and girls preferring Design, However, these

differences are not related to learning style, and they are secondary to

age. To bridge gender differences, developers should consider ways to incorporate

attributes from Role-Play and Design into any activity designed for children.

Implications and Applications

Our results for the adult sample suggest that diverse pedagogical methods

are critical to successfully engaging the full spectrum of adult learners.

In particular, it is vital for developers to recognize that their own learning

style is just one of multiple ways to learn, and to consider designs for

interactives that will appeal to other types of learners. For example, computer

science students tend to be Intellectual learners (Kolb, 2005). Developers

who are Intellectual learners would need to look beyond their own intuitive

personal preferences to find ways to engage Social, Creative, and Practical

learners. Two different solutions to this problem are possible. First, developers

can create custom activities for each learning style, offering a suite of

a la carte activities ranging from searchable reference content for Intellectual

learners, puzzles or mystery activities for Practical learners, hands-on

design interactives for Social learners, and an opportunity to share ideas

and perspectives for Creative learners. Alternatively, developers can incorporate

attributes that appeal to each of the learning styles into a single integrated

activity.

This research study informed eduweb's development of such a project, a Web site about black holes in collaboration with the Space Telescope Science Institute (http://hubblesite.org/explore_astronomy/black_holes/). The site offers encyclopedic content in both a reference section and as an on-demand pop-up window within interactive modules. These modules present puzzling questions (e.g. How do you find an invisible object?) as well as hands-on experiments for active, trial and error exploration (Can you find a safe orbit around a black hole?). The site did not offer social interaction with other users, as this requires staff moderation – a challenge for many organizations. Since Discussion was not especially popular even with Creative learners, this was not a high priority.

The fact that adults and children generally agreed on the play value of our sample activities indicates that play value should be a central goal. On the other hand, Interactive Reference was relatively low in children's activity preferences and placed last in both play/work scores and sample activity ratings. Children's aversion to Interactive Reference should limit its use to homework and research sites and to topics in which children have an intrinsic interest.

For children, the open-ended, exploratory nature of Design and Role-Play activities seem to mesh well with their desire for playful activities, across learning styles. For topics with content that is suited to Puzzle-Mystery or Simulation activities, developers may want to incorporate design or role-play elements to broaden their play value and appeal.

Overall, learning style does influence preference for on-line activities, and is yet another way that one size does not fit all. The results of this study provide new insight into our unseen audiences, helping us anticipate the kinds of experiences to which they will respond. This insight is a valuable addition to Web developers' approach and can help them create experiences that will appeal to all kinds of learners.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on research supported by National

Science Foundation Grant No. 0337116. We are grateful for assistance from

the following institutions for linking to our on-line surveys and helping

attract a broad national population to the survey: Bell Museum of Natural

History, Brookfield Zoo, COSI Columbus, Franklin Institute Science Museum,

Minnesota Zoo, New York Hall of Science, Oregon Museum of Science and Industry,

John G. Shedd Aquarium, and TryScience.org. We are also grateful to the following

organizations for allowing us to modify their on-line activities for our

sample activities: Biosphere 2 Center, Brookfield Zoo, and The JASON Project.

Finally, we are particularly grateful to Terry Kessel and the 5th and

6th grade students at Friends Select School in Philadelphia for

participating in the laboratory test.

This paper was originally published by Archives and Museum Informatics in the proceedings of the Museums & the Web 2007 conference. © 2007 Archives and Museum Informatics.

References Cited

Hay/McBer Training Resources Group (1999). Learning

Style Inventory-Version 3. Consulted November 2, 2002. Consulted February

14, 2007. http://trgmcber.haygroup.com/lsi.

Bearman, D. and J. Trant. (2005). “Museums and the Web: Maturation, Consolidation and Evaluation”. In D. Bearman & J. Trant (Eds.) Museums and the Web, Selected Papers from Museums and the Web 2004. Toronto: Archives and Museum Informatics. Available http://www.archimuse.com/publishing/mw_2004_intro.html

Chu, K.C., C. Heeter, R. Egidio, and P. Mishra (2004). Girls and Games Literature Review. May 2004, consulted February 18, 2007. http://spacepioneers.msu.edu/girls_and_games_lit_review.htm.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Kolb, A. Y. and D.A. Kolb (2005). The Kolb Learning Style Inventory – Version 3.1, 2005 Technical Specifications. Consulted February 14, 2007. http://www.learningfromexperience.com

Kolb, D. A., R. E. Boyatzis, and C. Mainemelis. (1999).”Experiential Learning Theory: Previous research and new directions”. In R. J. Sternberg and L. F. Zhang (Eds.) Perspectives on cognitive, learning, and thinking style. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Schaller, D.T., S.W. Allison-Bunnell, M. Borun, and M. Chambers. (2002). “How do you like to learn? Comparing user preferences and visit length of educational Web sites”. In D. Bearman and J. Trant (Eds.) Museums and the Web, Selected Papers from Museums and the Web 2002. Pittsburgh: Archives and Museum Informatics. Available http://www.archimuse.com/mw2002/papers/schaller/schaller.html

Schaller, D.T. and S.W. Allison-Bunnell. (2003). “Practicing what we teach: Applying learning theory to on-line educational interactives”. In D. Bearman and J. Trant (Eds.) Museums and the Web, Selected Papers from Museums and the Web 2003. Pittsburgh: Archives and Museum Informatics. Available http://www.archimuse.com/mw2003/papers/schaller/schaller.html

Schaller, D.T., S.W. Allison-Bunnell, A. Chow, P. Marty, and M. Heo. (2004). “To Flash or Not To Flash? Usability and User Engagement of HTML vs. Flash”. In D. Bearman and J. Trant (Eds.) Museums and the Web, Selected Papers from Museums and the Web 2004. Toronto: Archives and Museum Informatics.. Available http://www.archimuse.com/mw2004/papers/schaller/schaller.html

Schaller, D.T., S.W. Allison-Bunnell, and M. Borun. (2005). “Learning Styles and On-line Interactives”. In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.) Museums and the Web 2005: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives and Museum Informatics, 2005. Last updated May 16, 2005. Consulted February 2, 2007. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2005/papers/schaller/schaller.html

Cite as:

Schaller, D.T., et al., One Size Does Not Fit All: Learning Style, Play, and On-line Interactives.

In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings.

Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 31, 2007 at

http://www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/schaller/schaller.html